Cape Town – Thursday, 17 March 2022, The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) have released a scathing report on how the marketing of formula milk influences decisions on infant feeding.

The multi-country study was conducted in eight countries – South Africa, Bangladesh, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Northern Ireland, Vietnam and the United Kingdom. The report offers unprecedented insight into how the $55 billion formula industry impacts infant feeding practices. It found that formula companies use manipulative marketing tactics that distort science and medicine in order to legitimise their claims and push their products and ultimately, undermine parents’ confidence in breastfeeding.

It is clear from this report that multinational corporations continue to prioritise profits over population health. We can no longer ignore the adverse health effects associated with global for-profit players and their unconscionable actions, particularly as they relate to the most vulnerable members of society, that is, women and children.

A comprehensive marketing analysis was conducted in each country to understand the dynamics of formula milk marketing. In South Africa, 21% of the pregnant and postnatal women surveyed reported exposure to formula marketing in the preceding year. A major problem in the South African context is cross-promotion, which includes false and incomplete scientific claims about the benefits of formula milk. The following quote from the WHO report confirms this, “Industry has developed a wide range of formula milk product options which are strategically marketed together, and which serve to normalise their use during pregnancy and throughout infancy and early childhood. Some women spoke of how it was sometimes unclear which formula product was intended for which age of infant. Formula milks are positioned as close to, equivalent and sometimes superior to breast milk, presenting incomplete scientific evidence and inferring unsupported health outcomes”. This type of marketing contravenes the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

While we must hold the private sector accountable for unethical marketing, such tactics are not the only barrier to breastfeeding. Despite the National Department of Health’s comprehensive infant and young child feeding policies and guidelines, currently only 31.6% of infants are exclusively breastfed, with a mean exclusive breastfeeding duration of 2.9 months. Local researchers conducted a study aimed at gaining an in-depth understanding of the experiences of South African working mothers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding when returning from maternity leave. Research shows that the South African workplace remains largely unaccommodating to breastfeeding employees – even though South Africa’s Code of Good Practice on the Protection of Employees during Pregnancy and After the Birth of a Child protects a mother’s right to breastfeed and express milk at her workplace.

Our work brings us into contact with first time mothers, who face a dearth of education and support at the very beginning of their breastfeeding journeys. Mothers express their frustration with the conflicting or incomplete information from healthcare providers who have failed to provide adequate breastfeeding education and support. Their anxieties are compounded when their baby does not latch properly or there is insufficient milk supply, or the mother experiences excruciating nipple pain and signs of mastitis. We recognise that the healthcare system is overburdened and under-resourced. What we need is adequate financing for the state’s commitments to improving the national breastfeeding rate, particularly the training and deployment of qualified and culturally-competent human resources in our country’s public health facilities, for example, multi-lingual specialist lactation consultants who are available immediately after birth and in the first 14 weeks postpartum.

The WHO report rightfully calls for the recognition of the magnitude and urgency of the harmful and invasive nature of formula milk marketing, and for countries to adopt or strengthen comprehensive national mechanisms to combat this problem. Should we expose and regulate conglomerates that jeopardise child and maternal health and human rights? Absolutely, yes. But, we must go several steps further. WHO found that formula milk companies organised and managed baby clubs, which offered women information on pregnancy and birth, and access to “carelines” and apps which provided 24/7 “support and advice”, although sponsorship by the rapidly growing formula milk industry was not always disclosed. This was not a sincere attempt by formula companies to support mothers, but was found to form part of a strategy to “nurture pain points – problems, real or perceived – out of common infant behaviours such as crying and tiredness, and position their products as the solution”. Whilst these tactics need to be strongly addressed, the popularity of these online communities shows that mothers want compassionate support accessible to them when they need it, even in the middle of the night.

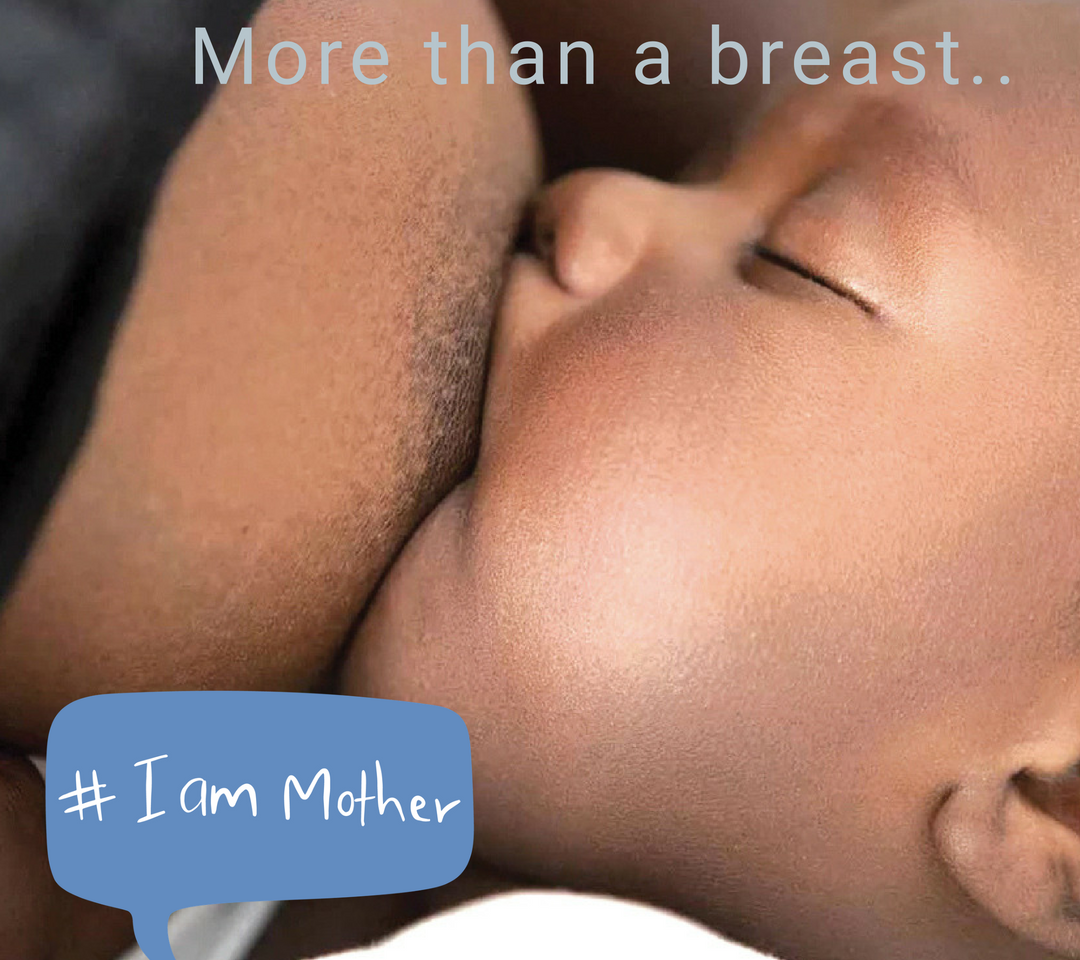

Mothers are entitled to impartial health information, that is free of commercial influences. The WHO report confirms that most mothers have a strong desire to breastfeed, but they often encounter a lack of support and enabling environments to empower them to do so.

In order to increase our chances of breastfeeding success, we need to give serious consideration to what it means to give mothers comprehensive breastfeeding support that provides them a sense of safety, acceptance, understanding and sensitivity, and that transcends the frequently espoused, overly simplified epithet “breast is best”.

For more information and media queries, contact: Nonkululeko Mbuli (Communications and Advocacy Strategist)

Cell: 079 367 1991

Email: nonkululeko@embrace.org.za

Permalink